We’ve written extensively about question types, the elements of good and bad writing, why people forget, and common problems with survey questions.

We’ve written extensively about question types, the elements of good and bad writing, why people forget, and common problems with survey questions.

But how do you get started writing questions? Few professionals we know have taken a formal course in survey development and instead rely on their experiences or best practices.

Despite being called questions, survey questions can be both questions and phrases, which is why some researchers refer to them with the broader item. Other researchers (e.g., Saris and Gallhofer, 2004) have referred to them as assertions, but that seems a bit cumbersome and unfamiliar. In our practice, we use question and item interchangeably.

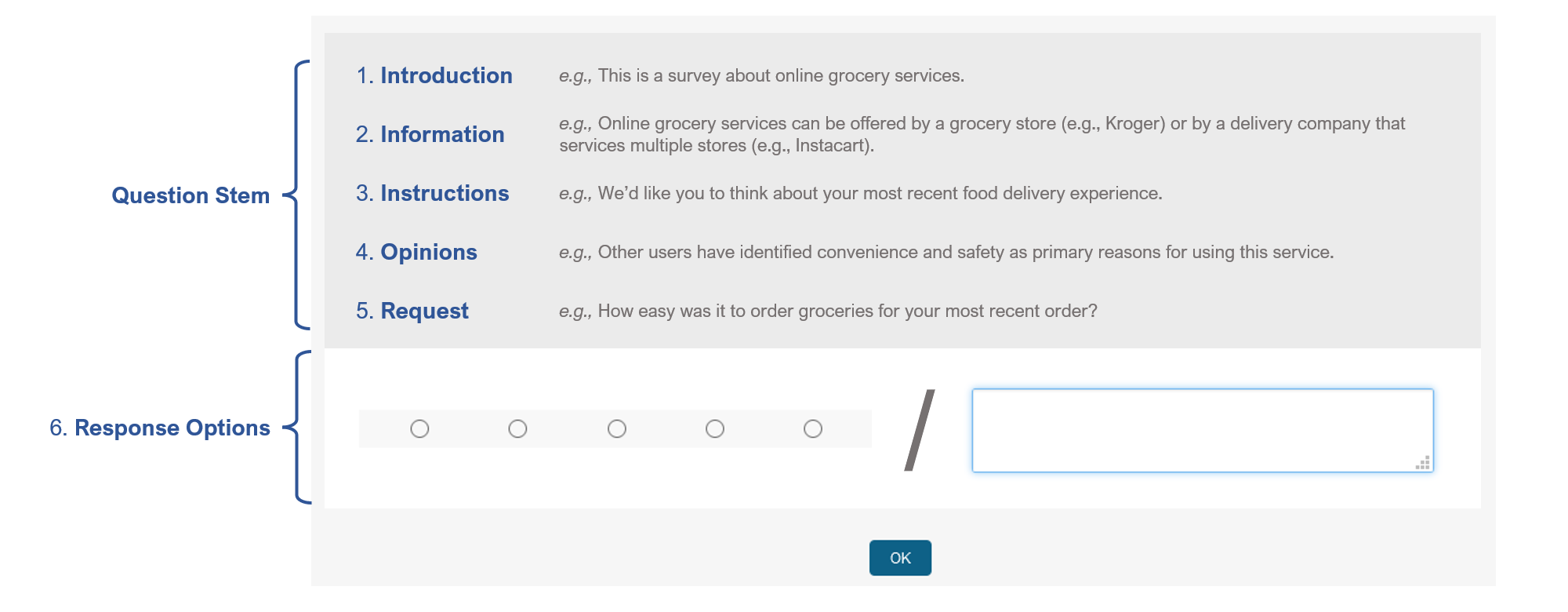

It helps to first think of the “anatomy” of a survey item. Items have two parts: the stem and the response options (e.g., Robinson and Leonard, 2019). Saris and Gallhofer (2007) break down survey items further into six components: five describe the stem, and the last is for response options.

- Introduction

- Information

- Instructions

- Opinions

- Request

- Response Options

Not all survey questions have all six components, and by understanding the components and their functions, you will know when and how to use them. Here’s more detail on the anatomy of a survey question.

Figure 1: Anatomy of a survey question overview.

1. Introduction

Surveys are typically on a specific topic, and an introductory statement helps the respondent get in the right frame of mind. For example, “This is a survey about online grocery services.” But questions themselves may need their own introduction (for example, “Now we’d like to ask you some questions about your experience ordering groceries online”).

Introductions may be needed when you

- Shift the topic from prior questions (e.g., you go from asking about the experience of using a desktop website to a mobile app).

- Require more thinking/recall from respondents.

2. Information about the Topic or Definitions

After the introduction, you may need to provide additional information about what you’re asking. You won’t need this for simple attribute-type questions (age, income, gender), but you may need it for less familiar topics or ambiguous topics that respondents might interpret broadly. For example, when asking about the use of online grocery delivery, information may include something similar to “Online grocery services can be offered by a grocery store (e.g., Kroger) or by a delivery company that services multiple stores (e.g., Instacart).”

Information about the topic may be needed when presenting

- New concepts or less familiar concepts.

- Complex constructions.

- Options that may be easily confused.

3. Instructions

While most people don’t need instructions on how to indicate their age or to select a radio button in a Likert-type question, certain questions require instruction on how to answer. Common question types that benefit from instructions include

For example, when we conduct a Kano study using our MUIQ platform, we provide instructions on how to answer the functional and dysfunctional questions using a common scenario in which respondents rate features.

And when using task-based questions (typically in an unmoderated usability study), it’s a good idea to let participants know to try and complete the task as best as possible and state “We’d like you to think about your most recent food delivery experience.”

Instructions may be needed

- When using uncommon question types (e.g., Kano, pick some, fixed sum).

- To prevent common mistakes (e.g., picking only one instead of all that apply).

4. Opinions of Others

In some cases, you may want to understand how respondents react to the opinions of others, such as politicians, public health officials, or scientists. For example, “Other users have identified convenience and safety as primary reasons for using this service.”

Opinions of others may be needed when

- Reaction to the opinions of others is the primary research focus.

- Including this information provides an appropriate context for asking the question.

This element is especially rare in UX and CX research due to its potentially biasing effects on responses. Don’t include it unless there is a clear need to do so.

5. Requests for an Answer

The core part of the question stem is the request to the respondent for some answer. For example, “What was your highest degree obtained?” or “How easy was it to order groceries for your most recent order?”

To create the request, you can use three approaches:

Direct request: Invert the subject and auxiliary verb of a statement to convert it to a question. For example, “I would need the help of a technical person” becomes “Would you need the help of a technical person?”

Indirect request: Instead of asking a question, use a statement and then have people respond with agree/disagree response options. For example, respond to statements such as “I felt very confident using the software.”

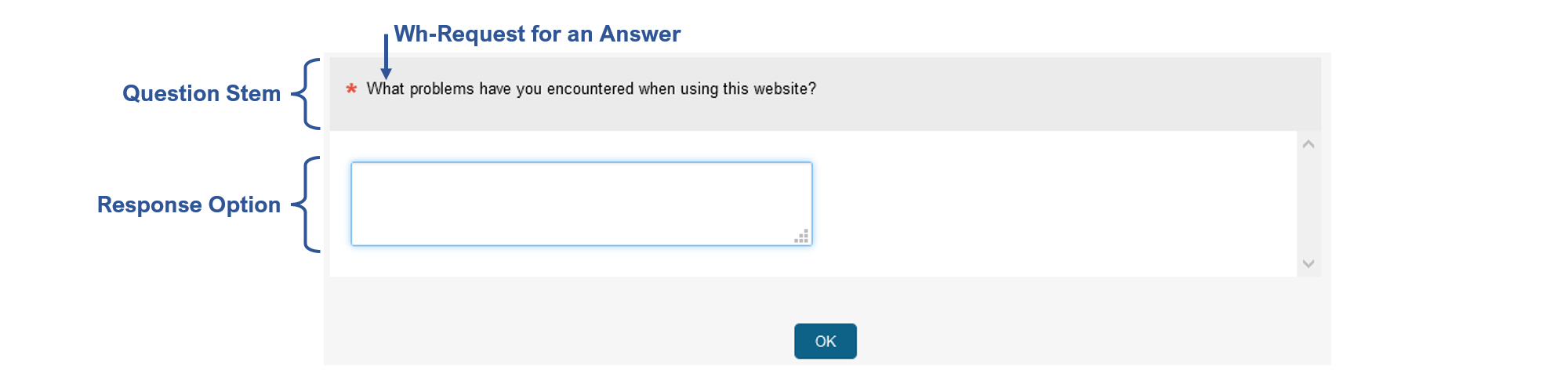

Wh-requests: Use the common interrogatives (e.g., who, what, when, how much, which) and pose the question directly to the respondent; for example, ask “What is your age?” or “Why did you select the number you did?”

This request for an answer is the last and most important of the stem components. The introduction, information, instructions, and opinions are optional, but without the request for an answer, you don’t have a question.

6. Response Options

In addition to crafting the item stem (Steps 1–5), selecting the right response options requires careful consideration of the intent of the question. Researchers can use various response option types, but some types are better suited than others for different research goals. We’ve identified four key steps to help you get started:

- Discovery: When discovery is the primary goal, use open-ended items.

- Measurement: The key decision when collecting measurements is to determine if the required data is or isn’t categorical.

- Categorical: Categorical data can be ordered (e.g., age groups) or unordered (e.g., streaming video services), allowing selection of multiple items when choices aren’t mutually exclusive or restricting selection to one item when choices are mutually exclusive.

- Not categorical: Noncategorical question types can be classified as ranking, allocation, or rating. Of these types, rating scales are the ones most used in UX and CX research.

In a previous article, we put together a decision tree that should help narrow your choices on selecting the right response option.

Examples

Example 1. If your goal is to discover the types of problems users have been having with a website, then the response option type should be open-ended (Goal > Discovery > Open-Ended Item), with item stem and response option similar to those shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Stem and response option for a discovery question.

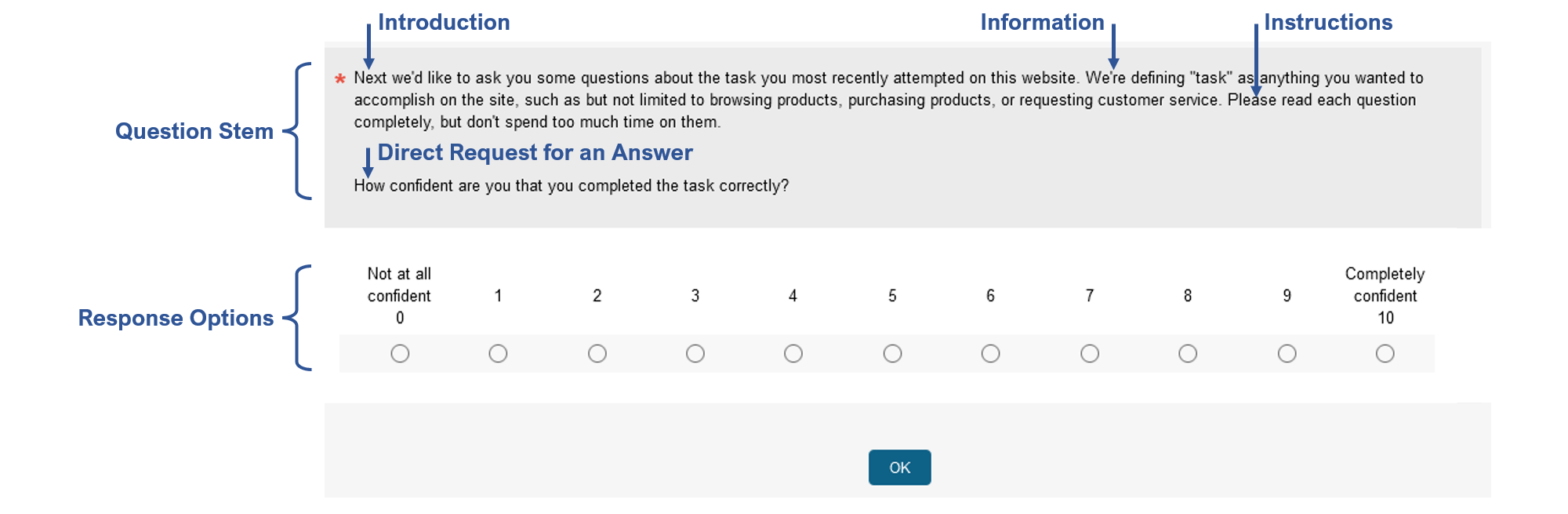

Example 2. If your goal is to measure a respondent’s confidence in having correctly completed a task and you’ve conceptualized this measure as ranging from no confidence to total confidence, the response type should be a unipolar rating item (Goal > Measurement > Not Categorical > Rating > None to Much > Unipolar Item), such as the one illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Stem and response option for a unipolar rating question.

Summary

There is a pattern to the structure of survey questions. At a high level, survey questions contain a stem and one or more response options.

The stem must contain a request for an answer. It may also include an introduction, information pertinent to the question, some instructions, and information about the opinions of others (rare in UX/CX surveys but more common in social and political surveys).

Requests for answers can take several forms, including direct requests, indirect requests, and wh-requests.

Researchers can choose from a wide variety of response options. To help with that process, they can use a decision tree designed for that purpose.

These concepts, strategies, and tools can help UX researchers overcome writer’s block when crafting the items for surveys and related research activities.