What makes a product successful? How does a new technology get adopted?

What makes a product successful? How does a new technology get adopted?

Whether business software, a mobile app, or a physical product, there are plenty of examples of products that had a lot of promise but failed, and others that many consider a success.

Plenty of books expound theories on developing a successful product (e.g., Crossing the Chasm; The Lean Startup). Unfortunately, these types of books also contain plenty of untested conventional wisdom.

Two common ingredients of success that have emerged across many of these theories and books (even if they are not explicitly mentioned) are usefulness and usability. That is, a product should do something people think is useful (that may change over time), and people should think the product is easy to use (usable).

So how do you measure usability? How do you measure usefulness? More specifically, how do you measure perceptions of usefulness and perceptions of usability?

A way to measure both is to use the UX-Lite™.

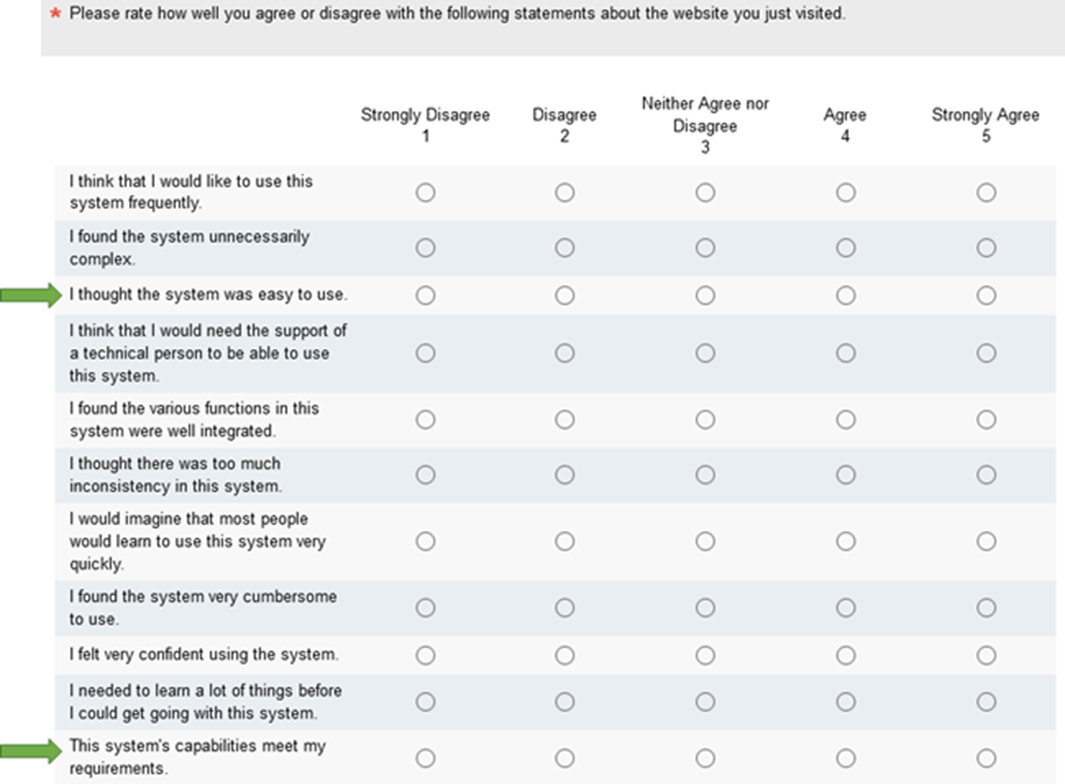

The UX-Lite is a two-item standardized questionnaire adapted from the UMUX-Lite (Lewis, Utesch, & Maher, 2013). We introduced it in our webinar in September 2021.

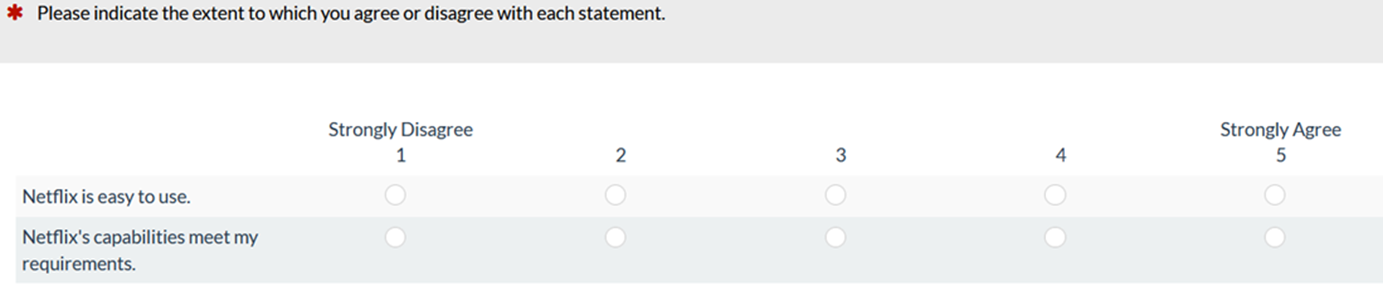

As shown in Figure 1, one item assesses perceived ease-of-use, and the other assesses perceived usefulness (functional adequacy).

Where did the UX-Lite come from?

In this article, we trace the evolution of the UX-Lite, starting from standardized questionnaires created in the mid-1980s. Its path of development is summarized in Figure 2.

In the Beginning: SUS and TAM

In the mid-1980s, researchers in two different disciplines were grappling with similar issues.

Usability engineers needed standardized methods for assessing perceived usability. To address that need, in 1986 John Brooke developed the System Usability Scale (SUS) for use in his lab, but he also shared it with other researchers. The SUS is fairly short, containing ten five-point agreement items. Brooke didn’t publish it until 1996, but by then it was already in use in several usability labs. It is now one of the most used and cited measures of perceived usability.

At roughly the same time, researchers in the management of information systems (MIS) were grappling with the reluctance of users to accept new technologies in the workplace. Fred Davis tackled this in his doctoral dissertation as he developed the first version of the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), proposed in 1985 and published in 1989.

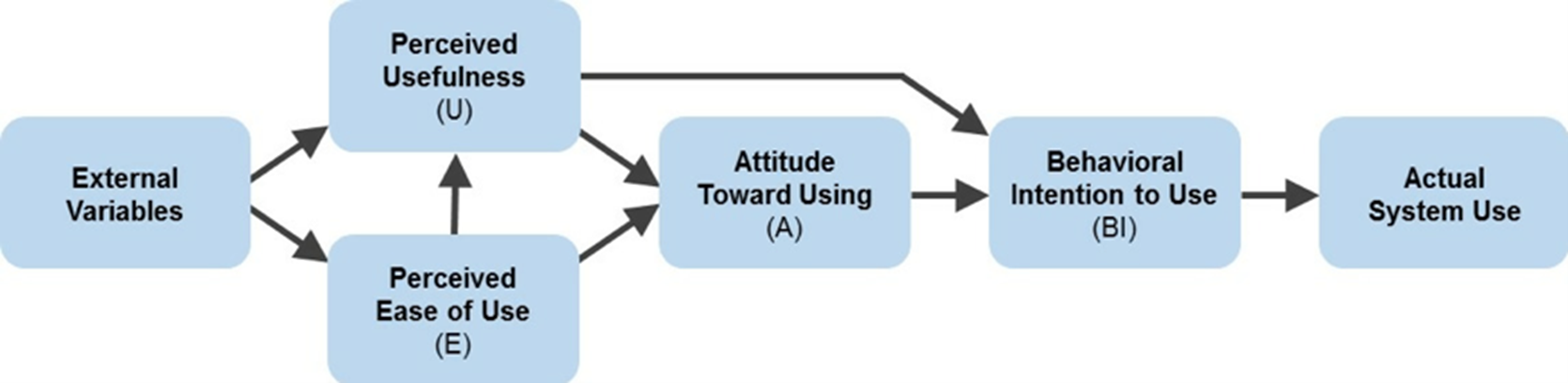

The heart of the TAM is the relationship between users’ beliefs that the new technology will be useful (perceived usefulness) and usable (perceived ease-of-use), which affect, in order, attitudes toward use, the intention to use, and actual use (Figure 3). As far as we know the TAM is the first standardized questionnaire to attempt to measure these two concepts.

The original TAM had twelve items (six for perceived usefulness and six for perceived ease-of-use), but since its inception several decades ago, there have been several modifications, including reducing the number of items for each construct from six to four and adapting the TAM to be a retrospective measure of actual experience (mTAM) rather than ratings of the likelihood of future use.

The Next Step: ISO-9241-11 and the UMUX

The next step in the evolutionary chain occurred in 2010 when Kraig Finstad published the Usability Metric for User Experience (UMUX, Figure 4), which was inspired by the SUS and the international standard for the definition of usability (ISO-9241-11, edited by Nigel Bevan).

Even though the SUS is a relatively short questionnaire, UX researchers need a shorter instrument in some situations, especially when designing a study that will measure many attributes of use, leaving limited “real estate” for any given attribute.

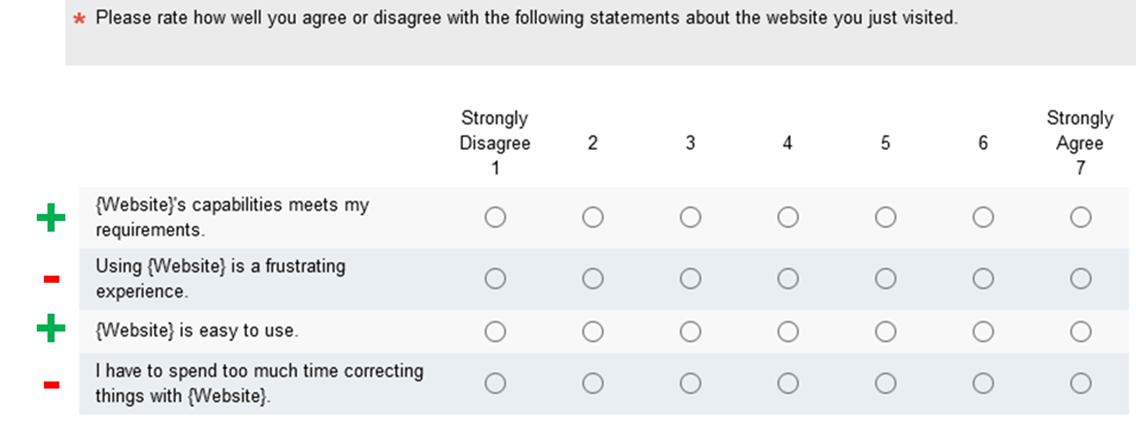

Finstad’s approach to solving this problem was to create a pool of items based on the three key attributes of usability as defined in ISO-9241-11 (four candidate items per attribute): effectiveness, efficiency, and satisfaction. From these sets, he identified the items that had the highest correlation with concurrently collected SUS scores (Effectiveness: {Website}’s capabilities meet my requirements; Efficiency: I have to spend too much time correcting things with {Website}; Satisfaction: Using {Website} is a frustrating experience). Then, to balance the number of positive-and negative-tone items, he added an overall item focused on ease of use: {Website} is easy to use.

Like the standard SUS, UMUX items vary in tone, but unlike the SUS, UMUX items have seven rather than five scale steps from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree); item scores are then manipulated to obtain an overall score that ranges from 0 to 100. In addition to the initial research by Finstad, other researchers have also reported desirable psychometric properties for the UMUX, including acceptable levels of reliability, concurrent validity, and sensitivity.

Morphing the UMUX into a Mini-TAM: The UMUX-Lite

Shortly after the publication of the UMUX, researchers at IBM made several attempts to replicate Finstad’s (2010) findings (Lewis, Utesch, & Maher, 2013). As a result of their construct and item analyses, they determined that a measure made up of just the positive items of the UMUX had excellent psychometric properties (reliability, concurrent validity, sensitivity). They named this two-item questionnaire the UMUX-Lite. Previous research on alternate versions of the SUS (Sauro & Lewis, 2011) has demonstrated the suitability of preferring questionnaires with a consistent tone over those with alternating positive and negative tones.

A key insight that emerged from this adaptation of the UMUX was the recognition of its similarity to the perceived usefulness and perceived ease-of-use components of the TAM. The item, “{Website}’s capabilities meet my requirements,” was originally intended to represent the ISO-9241-11 usability component of Effectiveness, but it could easily be reconceptualized as a measure of perceived usefulness. Recent regression analyses that model the components of the mTAM and UMUX-Lite as drivers of overall experience and likelihood-to-recommend support the interpretation of the UMUX-Lite as a mini-TAM (Lah, Lewis, and Šumak, 2020).

Removing the “UM” from the UMUX-Lite: The UX-Lite

Attracted by its conciseness and published psychometric properties, researchers at MeasuringU® began using the UMUX-Lite in 2016, a few years after its publication. In doing so, we made a few modifications to make it easier to collect data with existing questionnaires such as the SUS and SUPR-Q®, creating the questionnaire now known as the UX-Lite.

Number of scale points. One modification was to switch from seven-point to five-point scales to match the SUS and SUPR-Q formats so that researchers could present the UX-Lite items in the same grids as those other standardized questionnaires. This also allows researchers to take advantage of the Ease items in the SUS and SUPR-Q rather than asking respondents to make essentially the same rating twice. Thus, simply adding the one UX-Lite Usefulness item to a SUS or SUPR-Q grid enables computation of the UX-Lite in addition to the traditional metrics (see Figure 5).

Alternate wording for the Usefulness item. Over the past year, we have explored the measurement properties of several alternate versions of the Usefulness item, driven by client requests and our concerns with the clear difference in the linguistic complexity of the two items. The set of alternates (including the original) that we currently endorse are

- {Product}’s capabilities meet my requirements.

- {Product}’s functionality meets my needs.

- {Product}’s features meet my needs.

- {Product}’s functions meet my needs.

- {Product} does what I need it to do.

Based on our research, all of these have acceptable measurement properties, but our currently recommended version is “{Product}’s features meet my needs.”

What’s Next?

With the research conducted so far, we do not anticipate any major changes to the UX-Lite. We are currently researching two topics:

- Will an even simpler version of the Usefulness item, “{Product} meets my needs,” have acceptable measurement properties?

- What is the best way to estimate SUS from the UX-Lite? Is it better to use the UX-Lite scores, which are a combination of Ease and Usefulness, or is it better to use only the Ease component, given that the SUS is generally interpreted as a measure of perceived usability?

We expect to publish the results of these investigations in the near future, and we will discuss them at our upcoming webinar in October 2021.

Summary

For a new product or technology to be adopted, it should be both useful and usable. The UX-Lite is a two-item questionnaire that measures both. In one sense, the UX-Lite is a new metric. In a broader sense, it’s a mature metric, having properties it has inherited from the evolutionary line of questionnaires that preceded it—specifically, the UMUX-Lite, the UMUX, the SUS, and the TAM. In the future, we will continue investigating its properties as a UX metric and learning how to use it effectively in UX and CX research. Consistent with Stephen Jay Gould’s evolutionary theory of punctuated equilibria, however, we expect the pace of change to be much slower in the immediate future.