UX has no shortage of models, methods, frameworks, or even catchy acronyms.

UX has no shortage of models, methods, frameworks, or even catchy acronyms.

SUS, TAM, ISO 9241, and SUPR-Q to name a few.

A relatively new addition is the HEART framework, derived by a team of researchers at Google. And when Google does something, others often follow.

HEART (Happiness, Engagement, Adoption, Retention, and Task Success) is described by Rodden et al. in a 2010 CHI Paper [pdf], which was written after applying the framework to 20 products at Google.

The HEART framework is meant to help integrate behavioral and attitudinal metrics into something scalable for large organizations (such as Google) that have many software and mobile apps.

Of course, most businesses don’t have a shortage of metrics. The problem, the authors argue, is knowing the right way to use those metrics to manage the user experience of many products.

For example, PULSE metrics (Page views, Uptime, Latency, Seven-day activity, and Earnings) are heavily tracked but indirectly related to the user experience and thus hard to use as dependent variables when making design changes. For example, are more page views a result of increased advertising or a problem with the design? And a perennial question: Is more time logged on the app better or worse?

Nothing helps adoption of a framework like a good acronym and some puns. You can’t have a PULSE without a HEART and the HEART is what Rodden et al. propose to make the most of the PULSE metrics. It’s composed of:

Happiness: These are attitudinal measures such as satisfaction, visual appeal, ease of use, and our friend likelihood to recommend.

Engagement: These metrics, such as the number of visits per user per week or the number of photos uploaded per user per day, provide some measure of engagement. These may not apply for enterprise users though, especially when the user doesn’t get to decide whether they must use the technology.

Adoption and Retention: New users per time period (e.g. month) describe the adoption rate whereas the percent of users after a specific duration (e.g., 6 months or 1 year) would be the retention rate.

Task Success: These are the commonly used metrics—such as task-completion rate, task time, and errors—that are already collected during most usability tests.

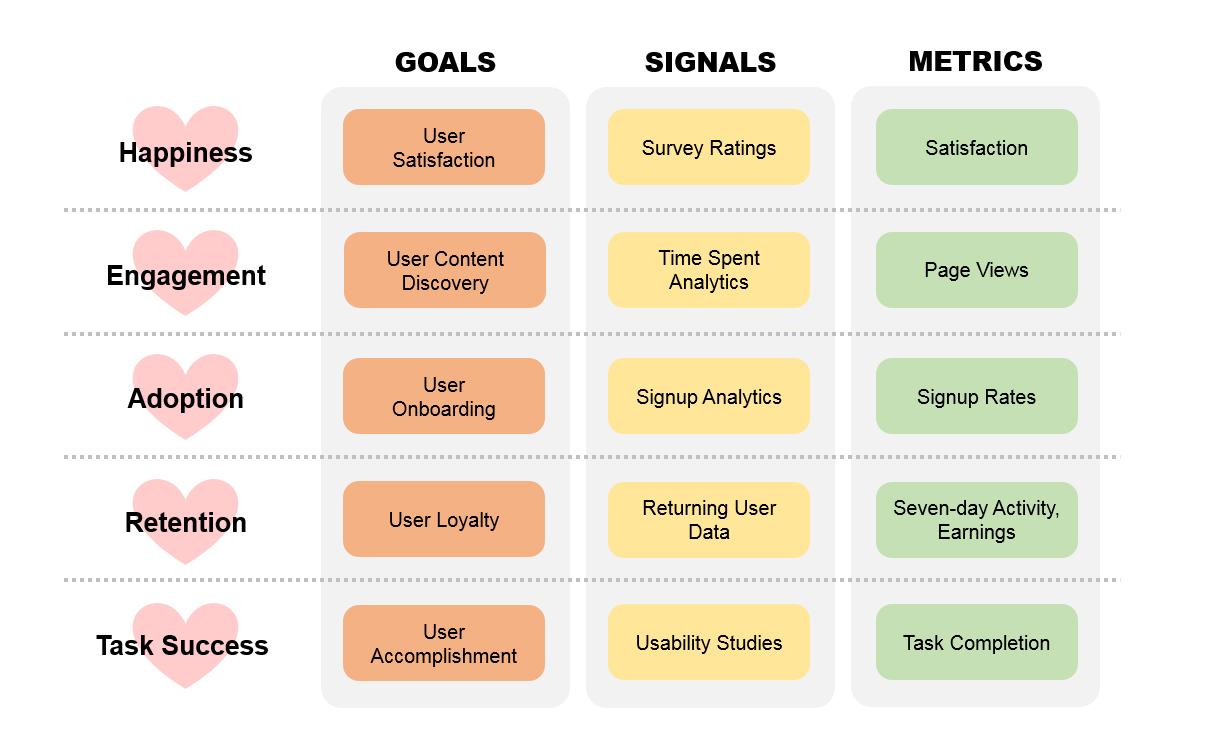

The PULSE and the HEART are woven into more conventional business ideas: Goals, Signals, and more Metrics (but without a catchy acronym). Rodden et al. describe the GSM as:

Goals: Critical tasks users want or need to accomplish.

Signals: Where you will find metrics (such as usage data and surveys) that would indicate whether the goals were met.

Metrics: The PULSE metrics, such as number of users using a product over a period of time.

Together this has been presented as a matrix with HEART, PULSE, and GSM as shown in Figure 1 (with examples we’ve added).

Figure 1: The HEART, PULSE metric examples integrated within a GSM matrix.

HEART Builds on Other Frameworks

There’s a temptation to dismiss new frameworks or methods on the one hand or jump after the next shiny thing on the other (especially when it’s advocated by successful companies). I see methods, frameworks, and metrics such as HEART as adaptations rather than replacements for existing ones. A good new method should build on existing ones and evolve it to be more efficient, effective, or specialized.

For example, the PURE method is an extension of the cognitive walkthrough and expert review, which we’ve found is a reasonable proxy for actual user task performance. And, of course, we also came up with a catchy acronym.

While the authors don’t explicitly link HEART to other frameworks and methods, it’s not hard to see some connection. For example, the HEART framework certainly isn’t the first to associate UX metrics to business metrics and user goals. And over 30 years ago, using metrics in the design phase was one of the key principles identified by Gould and Lewis.

Many organizations are already collecting the NPS and conducting regular usability testing that contain the task-based metrics of completion rates and task times. We actually collected usage data at the same time as the HEART publication. These usability metrics are part of the ISO 9241 pt 11 definition of usability. Finally, the top-tasks analysis is also a great way at defining critical user goals (the G in the GSM).

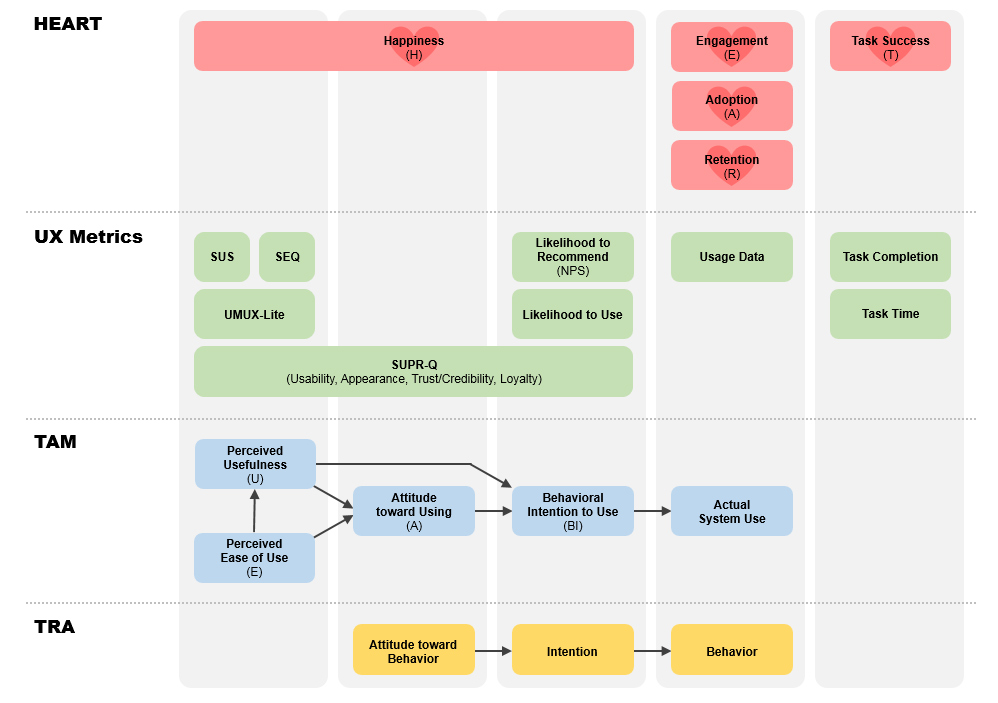

HEART can be seen as a manifestation of the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM)—after all, both include Adoption in their names. The TAM is itself a manifestation of the Theory of Reasoned Action. The TRA is a model that predicts behavior from attitudes.

The TAM suggests that people will adopt and continue to use technology (the EAR of the HEART) based on the perception of how easy it is to use (H), how easy it actually is to use (T), and whether it’s perceived as useful (H). The SUS, SEQ, and the ease components of the UMUX-Lite and SUPR-Q are all great examples of measuring perceived ease (and bring the Happiness to the HEART model).

I’ve mapped together what I see as the overlaps among the TRA, TAM, and other commonly collected UX metrics in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Linking the HEART framework with other existing models (TAM, TRA, and metrics that link them).

HEART Is Light on Validation

As we encounter new methods, we like to look for any data that validates why the method works and how it might be better or at least comparable to existing ones. The foundational paper offered some examples of how to apply aspects of HEART, but it didn’t offer much in the way of validation data. For example, it would have been good to see stats, such as how teams at Google that used the HEART method achieved their goals x% faster, or engaged employees, or even resulted in more successful (more revenue, less time to market) products. While this sort of data can be hard to collect, Google has conducted and published similar comparison studies on the decision behind hiring personnel. If you have any data, please share it!

But even without data showing that the HEART method is better or more effective, it does have one thing going for it: It’s a relatively simple framework with a memorable name. Executives and product teams are often so overwhelmed with data and methods that simple and good enough get used more than complicated and perfect. This is especially important when trying to measure many disparate products across large organizations (such as enterprise software).

Simplicity and memorability are likely one of the reasons the NPS became so popular. The “How likely are you to recommend?” question has been asked for decades as part of measuring customer word of mouth. Yet it took Fred Reichheld and the well-branded Net Promoter Score to get executives to care about customers’ behavioral intentions. If the HEART framework has a similar effect of making UX teams more successful at using data to make design decisions, then I can learn to love the HEART too!

Summary and Takeaways

A review of a framework for measuring the user experience on a large scale revealed:

The HEART framework. HEART is a way to use attitudinal measures (Happiness) to predict adoption and usage statistics (Engagement, Adoption, and Retention) that can be tracked using task-based measures in usability testing such as Task completion rate and task time.

The HEART framework builds off existing models. Even though it wasn’t explicitly linked to existing models, HEART extends the thinking of the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), which is itself an extension of the Theory of Reasoned Action and uses many common UX ISO 9241 metrics.

You’re likely already using many of the components. Many organizations are already collecting UX metrics in usability tests, collecting behavioral intentions (e.g., NPS), and measuring usage and retention and even conducting top-tasks analysis to align efforts to user goals.

If the HEART gets you more UX love, use it. If the HEART framework helps get your organization to measure more or better prioritize development efforts based on users’ attitude and behavioral intention then you should love the HEART. Without data showing that the framework is better than others, it doesn’t necessarily mean you should drop your current UX measurement framework (if you have one). If you’ve had success with the HEART, share the love!