“I’d like you to think aloud as you use the software.”

“I’d like you to think aloud as you use the software.”

Having participants think aloud as they use an interface is a cornerstone technique of usability testing.

It’s been around for much of the history of user research to help uncover problems in an interface.

Despite its popularity, there is surprisingly little consistency on how to properly apply the think aloud technique. Because of that, there is some controversy on how effective or necessary it actually is.

To better understand both the method and its application, it helps to know where it came from and how it’s evolved. And like the field of User Experience in general, the roots of thinking aloud has its genesis in other fields with over a century of history and evolution.

1890s Psychoanalysis and Free Association

Observing a usability test to some may look and sound a lot like a therapy session. That’s not a coincidence. The image of a patient lying on Sigmund Freud’s couch and uncovering repressed feelings is quite familiar to the general public; it’s also where the practice of thinking aloud likely took root.

Freud believed patients could access the unconscious while conscious, and developed the practice of psychoanalysis and talk therapy. The goal was to bring unconscious thoughts to the surface. Prior to Freud, hypnosis was used as a popular treatment technique—something I don’t believe has been attempted yet with usability testing but it could be interesting!

In Freud’s free association, patients allowed their thoughts to flow freely without censorship or conscious intervention. It didn’t matter if the thoughts weren’t coherent; the idea was to share them aloud as they come to mind. Freud’s goal was to gain insight into unconscious processes, something similar to what participants are now asked to do when interacting with interfaces.

Early 1900s Introspection

As psychology continued to evolve as a science so did the theory and practice of thinking aloud. Wilhelm Wundt founded the first psychology lab and used a method called introspection to get at the inner workings of a patient’s mind. He had patients verbalize their sensations and thought processes, report their inner thoughts, and look inward at pieces of information as they passed through consciousness.

Wundt would also have trained participants describe the sensations they experienced when looking at simple physical stimuli, like an object. For example, people could look at a daisy and articulate it as round, with silky petals, 5 leaves on the stem, white petals, and yellow in center. He also asked them to describe the feelings associated with these perceptions, such as it making them feel happy or young at heart. Wundt then analyzed the relationship between sensations and feelings. Wundt’s student, Titchener, brought a form of the idea of introspection to the U.S. and developed it as a more systematic method. This practice is similar to commenting on a user interface in usability testing today.

1920-1950 Behaviorism Backlash

As psychology evolved, so did competing theories. Freud and Wundt relied on people’s ability to articulate their inner thoughts, something that’s hard to verify. The behaviorist movement, best known by its pioneer, B.F. Skinner, argued against introspection as being too subjective.

As the name implied, the behaviorists emphasized the importance of behavior as something that could be measured objectively. Investigations of the mind, and thus thinking aloud, fell out of favor. This tension between what people say and what they do continues to exist decades later as we measure the user experience.

1920s-1930s Private Speech

At around the same time as the behaviorist movement, Lev Vygotsky and Jean Piaget observed “private speech” in children. If you have children, you’ve likely seen your kids talking to themselves (that’s a good thing). Children from around ages 2-7 engage in speech, which isn’t directed at anyone but is thought to help with self-regulation, and is related to memory, early literacy development and creativity.

Usually around school age, this “private speech” becomes internal. Many adults report experiencing an “inner voice,” which is also sometimes expressed aloud when alone or thinking through a tough problem. The strength of one’s inner voice likely has an impact on a participant’s ability to think aloud and will be discussed in a future article. Not all participants have the same ability to articulate their thoughts, which may be related to differences in their inner speech.

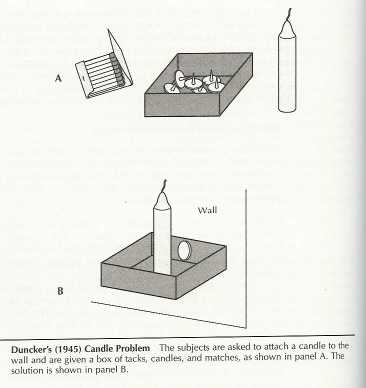

1940s-1960s Thinking Aloud to Solve a Problem

Karl Duncker, a Gestalt psychologist also described a “think aloud” methodology. He had participants think aloud as they solved problems. “…allowing [the participant’s] activity to become verbal.”

Duncker came up with the now famous (in psych circles) “candle problem.” In the problem, participants were given a book of matches, a box of thumbtacks, and a candle and asked to affix and light the candle on a wall so the candle wax wouldn’t drip onto the table below.

This verbalizing of thoughts was different than introspection, because participants weren’t asked to analyze their own thoughts but instead asked to focus on the problem and verbalize their thoughts.

Participants who thought aloud actually had better success at solving this task than others! This suggests the mere act of asking people to think aloud likely changes their behavior, which has clear implications for its application in having users attempt tasks when evaluating interfaces.

With the influence from cognitive psychology, scientists sought to explore the relationships between brain and behavior by studying the “black box” of cognitive processes. Interest grew in methods that could provide data about internal thought processes.

1970s Telling More than We Know

The Think Aloud method again brought criticism. In 1977, Nisbett and Wilson[pdf] published “Telling More Than We Can Know: Verbal Reports on Mental Processes,” and argued against thinking aloud because participants didn’t have conscious access to high-level cognitive processes that regulate how stimuli affect responses.

For example, think of what you had for breakfast this morning. Can you describe how you came up with your answer? Describing how you came up with how you recalled having breakfast is certainly different (and difficult to ascertain) than simply recalling the pancakes you ate.

1980s-1990s Thinking Aloud Comes to Usability Testing

Ericsson and Simon (1984 and 1993) responded to Nisbett and Wilson’s critique of thinking aloud in their influential book, Protocol Analysis: Verbal Reports as Data.

Ericsson and Simon argued that certain types of verbal expression were accurate—just not the type used by Nisbett and Wilson. They argued that while there are clearly limitations to how far thinking aloud can take us, that doesn’t mean that it isn’t a useful tool.

They modeled thinking aloud into three levels:

- Level 1: Direct articulation of information stored in a language

- Level 2: Articulation or verbal receding of nonpropositional information without additional processing

- Level 3: Articulation after scanning, filtering, inference, or generative processes have modified the information available

When the information being processed to perform the main task is not verbal or propositional, it will likely slow down and affect performance. But when tasks fall into Level 1 thinking aloud, thinking aloud will not change the “course and structure of cognitive processes.”

In their protocol, the interaction between the researcher and participant is minimal, and participants are not asked to filter, analyze, explain, or interpret their thoughts, even if what they say is difficult for the researcher to understand.

2000- Applications in Usability Testing & Beyond

Thinking aloud is used extensively today by researchers as a key part of usability testing. Having participants think aloud provides a wealth of qualitative data into the thought processes and potential causes of problems.

Dumas and Loring’s Moderating Usability Tests provides detailed guidelines for moderators and “golden rules” on moderation, which includes some discussion on thinking aloud.

Research by Boren & Ramey found inconsistencies in how practitioners apply the Think Aloud method. They also found that in practice it deviates from the theoretical basis provided by Ericsson and Simon. Boren & Ramey argue, rather than basing current practice on Ericsson and Simon, a better theoretical justification is speech communication theory. In their model, the participant (the primary speaker) and the facilitator (the listener and secondary speaker) each has a defined role.

Despite its wide usage and rich history, several questions remain on thinking aloud, including:

- How necessary is it to uncover problems?

- How may it affect user behavior and how much?

- Are metrics distorted during thinking aloud?

- What percent of the population can effectively think aloud?

- How well does think aloud work for remote unmoderated usability studies?

- Does culture affect think aloud outcomes?

These topics are all ongoing research activities and will be addressed in future articles.

Thanks to Chelsea Meenan, PhD and Jim Lewis, PhD for contributing and commenting on earlier versions of this article.