In 1916, a leading periodical called The Literary Digest polled its large subscriber base of hundreds of thousands of readers and successfully predicted the winner of that year’s presidential election. The magazine repeated the poll in 1920, 1924, 1928, and 1932, correctly predicting the winner each time—five successful election predictions in a row.

In 1916, a leading periodical called The Literary Digest polled its large subscriber base of hundreds of thousands of readers and successfully predicted the winner of that year’s presidential election. The magazine repeated the poll in 1920, 1924, 1928, and 1932, correctly predicting the winner each time—five successful election predictions in a row.

In 1936, its poll had Kansas Governor Alfred Landon as the overwhelming winner. But that year, Franklin Roosevelt won easily, losing only two states to Landon. The magnitude of the magazine’s error (off by almost 20 percentage points!) allegedly destroyed the magazine’s credibility, leading to its shutting down 18 months after the election.

What happened? The 1936 poll had over 2 million respondents, a huge sample size! The problem wasn’t the size of the sample, but how the characteristics of the sample deviated from the US electorate over the years. The sample became biased as its readers became more educated and wealthier than the general voting population.

Not all biases are as obvious as the one in the Literary Digest example, but you’ve likely heard similar stories of inaccurate polls and survey results. For example, consider the following two examples:

“We surveyed our customer base and found a satisfaction score of 75%.”

“How outstanding was your experience with our customer service representative?”

In the first example, only customers for whom the company had contact information were surveyed. What about those who are no longer customers or those who didn’t provide their contact information? In the second example, the wording of the question goads the respondent into giving a positive response.

Potential Sources of Bias in Survey Design, and How Might They Be Controlled?

When designing a survey, you must be aware of biases and attempt to control them. The Literary Digest poll is a cautionary tale in failing to sample from a representative population. Four common biases are:

- Representativeness of sample

- Sponsorship

- Social desirability, prestige, acquiescence

- Demographic

Table 1 describes a bit more about each and some strategies to correct for these biases.

| Bias | Problem | Correction |

|---|---|---|

| Representativeness | Restrictions in the sample might affect representativeness (availability, tech savvy). | Consider using a variety of participant sources (and compare sources); use random stratified/ proportional sampling, not convenience sampling. |

| Sponsorship | Knowing where the survey is coming from can influence responses (especially problematic for brand awareness studies). | Obfuscate sponsor and/or use third-party research firm. |

| Social Desirability, Prestige, and Acquiescence | Participants have a propensity to provide socially acceptable responses and to tell you what they think you want to hear. | Frame participation as helping you improve the product, service, or policy. |

| Demographic | Asking certain demographic questions may prime people to respond untruthfully, not respond, or even drop out. | Representativeness is important but ask only the questions you need. Ask demographics last (unless needed for screening). |

Four Potential Survey Errors

Even a well-thought-out survey will have to deal with the inevitable challenge these potential errors will pose for the veracity of your data.

Adapted from Dillman et al. (2014), here are four errors to watch for and how to handle them when conducting surveys (and other methods that incorporate survey-like questions and sampling).

- Coverage: Not targeting the right people.

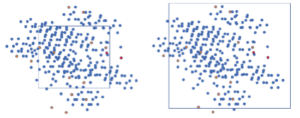

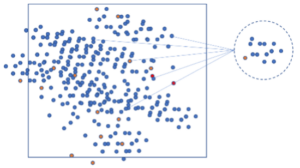

- Sampling: Inevitable random fluctuations you get when surveying only a part of the sample frame.

- Non-response: Systematic differences from those who don’t respond to all or some questions.

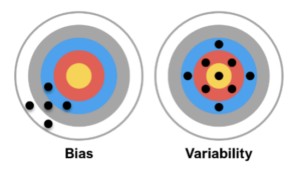

- Measurement: The gap between what you want to measure and what you get due to bias and response variability.

Unlike the four horsemen of the Apocalypse, these potential errors don’t result in pestilence and war, but they can still wreak mayhem on your results through errors in who answers (coverage, sampling, and non-response) and how people respond (measurement). Table 2 provides illustrations and error reduction strategies for the four errors.

Table 2: Error reduction strategiesBias Doesn’t Mean Abandon

Just because a survey has bias doesn’t mean the results are meaningless. It does mean you need to understand how each type of bias may impact your results. This is especially important when you’re attempting to identify a percentage of a population (e.g., the actual percent that agrees with statements, has certain demographics like higher income, or has an actual influence on purchase decisions).

While there’s no magic cure for finding and removing all biases, being aware of them limits their negative impact. In future articles in this series, we’ll cover other sources of bias, such as question wording, variation in response options, and potential order effects.

Looking to Learn More?

We’ve written much on biases and errors and the entire survey creation process, from writing questions to selecting response options and collecting and analyzing data. You can find plenty more in our book, Surveying the User Experience. We also have a companion course that follows the book on MeasuringUniversity.com.