Should you ask what people think?

Should you ask what people think?

Are thoughts and feelings reliable indicators of future behavior?

Asking about people’s attitudes—especially about their intentions (likelihood to use, recommend, or purchase)—gets a bad rap in UX research.

There’s a sort of folk wisdom in User Experience research: People are poor predictors of their future behavior.

And this distrust in what people think is rooted in some well-cited articles. For example, Nielsen says that the first rule of usability is not to listen to users.

Consequently, it’s not surprising that some researchers recommend you never ask whether people will do something or what they want.

Articles and conference presentations tend to echo what many researchers have experienced: watching a user have a horrible experience with a product but still rate it highly on ease and likelihood to use or recommend scales. How can we put any faith in these forward-looking opinions when that happens?

But there’s a very strong business need to know what current and prospective customers want or will use and purchase.

Other methods, such as the MaxDiff and Kano, are popular with many companies (and our clients) for helping understand what features people want or need. The top-task analysis advocated by Gerry McGovern (and us) also relies on what users say, their opinions and attitudes about what’s important, and how they intend to do things.

Can we trust the measures of people’s attitudes? Do attitudes towards ease, usefulness, trust, and likelihood to use actually predict future behavior? Or should we just ignore what people say?

To understand how well attitudes (what people think and say) predict behavior (what people do) we need a good definition of attitude and understand how its measurement has evolved.

Understanding Attitude

Human attitude has been studied for decades and one helpful model that’s emerged to describe attitude is the tripartite (or ABC model) model of attitudes. The ABC model, as we wrote about, deconstructs attitude into three parts: Affective (how people feel), Behavioral intentions (what people intend to do, also called conative), and Cognitive (what people think). Or you can think of attitudes as beliefs, feelings, and intentions (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Tripartite model of attitude.

The reason attitude has been studied intensely is that it was believed to be the key to understanding why people do what they do (and predict what they will do). It’s a cornerstone of social psychology.

But when experiments started to show that measuring what people think didn’t perfectly (or even modestly) predict what they would do, many researchers questioned the validity of using attitudes to predict behavior.

For example, in the late 1960s, Allan Wicker [pdf] examined 42 experimental studies, which showed at best a weak correlation between attitude and behavior (rarely above r = .30). He concluded:

‘‘It is considerably more likely that attitudes will be unrelated or only slightly related to overt behaviors than that attitudes will be closely related to actions.’’ (p. 65)

Wicker’s meta-analysis and its stark conclusion was influential to many researchers who doubted the link between attitude and behavior and connecting the two lost favor during the 1970s.

But rarely does one study become the final word on a subject, even one based on a meta-analysis. Other researchers re-examined how attitude and behavior were measured in the studies cited by Wicker and identified some shortcomings.

In 1995, Kraus conducted another influential meta-analysis and found reasonable support for the link between behavior and attitude with an average correlation of r = .38 across 88 studies. He also found that not all studies are created equal and several variables would affect (moderate) the relationship between attitude and behavior. For example, correlations were higher (r > .5) when researchers didn’t use college students (the favored captive audience for the academic social scientist) and when the attitude and behavior were measured at the same level of specificity.

Ajzen has shown that part of the reason Wicker’s analyses failed to find strong links between behavior and action was the failure to aggregate behaviors and the use of broad measures to predict specific actions. That is, it can be very difficult to predict individual instances of behavior (Will this one person purchase from Amazon.com this week?) from a general measure of attitude (satisfaction with Amazon). Aggregating across people and time reveals patterns (people more satisfied with the Amazon website tend to purchase more). Even better, matching the question specificity with the behavior (Will you purchase at Amazon.com this week? compared to purchase rates across people) should also improve the relationship.

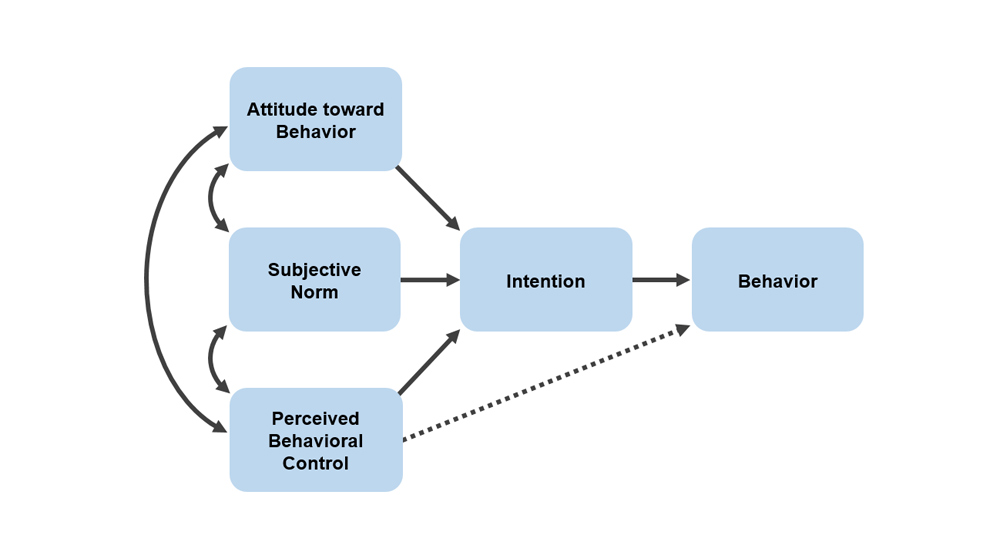

To better model the attitude to behavior connection, Ajzen extended the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA), which was used in the development of the Technology Acceptance Model, into something he called the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Ajzen’s model of the Theory of Planned Behavior.

With the Theory of Planned Behavior, Ajzen argues that while attitudes will themselves correlate with behavior, attitudes acting through behavioral intention usually tend to predict behavior better. That is, if people have an attitude (donating blood save lives), say they will do something (I will donate blood), they generally will (blood donated), with some caveats.

Other factors, for example the acceptability of the behavior (referred to in the model as subjective norm), will also play a role. In other words, if you want to know whether people will purchase at Walmart.com, ask people how likely they are to purchase at Walmart.com and whether they think it’s acceptable to purchase at Walmart.

The Theory of Planned Behavior is not without criticism as others have argued that beliefs themselves, under some circumstances, may be better predictors of action (as the Kraus meta-analysis showed).

But all theories are wrong and some are useful. The TPB has shown to be a reasonable model for predicting behavior. While the model will continue to evolve, Ajzen has put forth some compelling evidence that stated intentions can indeed predict behavior.

How Well Do Intentions Predict Behavior?

Ajzen, in his book Attitudes, Personality and Behavior, argues that when focusing on stated intention, behavior can be predicted reasonably well. Across several meta-analyses, and even meta-analyses of meta-analyses by Sheeran (2002), the average intention-to-behavior correlation is r = .53. Using one interpretation of this correlation, intentions can predict or explain about 28% of the variability in behaviors.

Table 1 shows correlations from several studies Ajzen cited, along with correlations from our own research on attitudes and behavior correlations and one other on predicting product usage.

For example, the correlation between intention to donate blood and actual donation in one study was strong at r = .75. The table also includes our three correlations from likelihood to recommend and reported recommendations over 90 days with correlations ranging from r = .69 (recently recommended product), r = .79 (recently purchased product), to r = .90 (select brands).

The correlation found that stated intention to use technology and actual adoption in one study was r = .5 (see the TAM article).

| Description | Correlation |

|---|---|

| Applying for Shares in British Electric Company* | 0.82 |

| Using Birth Control Pills* | 0.85 |

| Breast vs. Bottle Feeding* | 0.82 |

| Using Ecstacy Drugs* | 0.75 |

| Having an Abortion* | 0.96 |

| Complying with Speed Limits* | 0.69 |

| Attending Church* | 0.90 |

| Donating Blood* | 0.75 |

| Using Homeopathic Medicine* | 0.75 |

| Voting Choice in Presidential Election* | 0.80 |

| Likelihood to Recommend and Recommend Rate (Brands) | 0.90 |

| Likelihood to Recommend and Recommend Rate (Recent Recommendation) | 0.69 |

| Likelihood to Recommend and Recommend Rate (Recent Purchase) | 0.79 |

| Intentions to Use Technology and Actual Usage | 0.50 |

| SUPR-Q Quintiles and 90 Day Purchase Rates | 0.78 |

| Purchase Intention and Purchase Meta-Analysis (60 Studies) | 0.53 |

| Purchase Intent and Purchase Rate for New Products (n=18) | 0.75 |

Table 1: Selection of studies showing correlations between stated intentions and future behavior. * Studies are from Ajzen (2005, p. 100).

Note: The correlation is a measure of the strength of a linear relationship and is often measured using the Pearson “r” that can range from no correlation (r = 0) to r = 1 or r = -1, which is a perfect positive or perfect negative relationship. In general, correlations about .5 are considered “large” in the behavioral sciences.

Purchase Intentions

Table 1 also includes two correlations specifically for people’s likelihood to purchase (will consumers purchase a product). These are from a meta-analysis by Morwitz et al. (2007) that found that intentions predicted purchase behavior best for existing rather than new products, for durable products, specific brands vs. brand category, over shorter periods, and when the data is collected comparatively (product A vs B) rather than by itself.

Intentions weren’t always a good predictor. Most notably they found intentions to purchase new products were a poor predictor (the correlation was non-significant and negative).

Table 1 also includes our earlier analysis of aggregated SUPR-Q scores on future purchase rates. The SUPR-Q actually uses a mix of beliefs and feelings (ease, trust, appearance) and behavioral intention (likelihood to return and likelihood to recommend). It’s likely we would have seen stronger correlations between attitude and behavior if we examined purchase intentions. We’ll investigate ways of measuring purchasing behavior in more detail in future articles.

Do Attitudes Predict Behavior?

This data suggests that, in general, assuming people are acting on their own free will, they will follow through on their intentions. But not always. Correlations shown in Table 1 and across the meta-analyses cited are strong (r > .5), placing it among the strongest effects in behavioral sciences.

But even a strong correlation still means there will be a lot of discrepancy between intentions and actions. This is especially the case when trying to predict individual behavior from individual general attitudes. But just because attitudes aren’t a perfect predictor (that’s an unrealistic bar) doesn’t mean they aren’t useful. Don’t be afraid to ask what people think and will do but understand their limitations.

Summary and Conclusions

An analysis of the history and measurement of the attitude to behavioral connection found:

Attitude is a compound construct. Think of attitude as being composed of what people think and feel and intend to do. People’s thoughts and feelings affect their behavior. One popular model (the Theory of Planned Behavior) suggests thoughts and feelings (plus social acceptability) influence intentions that in turn affect behavior.

Intentions may predict behavior better than feelings and beliefs. For the most part, people’s intentions are a good (but far from perfect) predictor of behaviors under many circumstances. On average, behavioral intentions can explain a substantial amount of variation in future behavior. Across many studies the average attitude to behavior correlation is r = .53 and in many cases the correlation exceeds r = .7. This relationship even applies to what people will use and purchase.

Attitudes are not perfect predictors of behavior. Don’t expect all attitudes or intentions to always predict behaviors well. Attitude become a poorer predictor of behavior when asking about general intentions (intent to exercise) instead of measuring specific actions (e.g., climbing stairs or lifting weights) and when the behavior isn’t stable (when things change between intention and behavior). When asking about intention to use or purchase products, intentions may only be reliable with an existing rather than a new product.